Did you know that archival collections could be used for more than just historical research, or even that learning about the history of a place through their archives could be fun? At the Chatham University Archives & Special Collections, we know that sometimes learning about and celebrating history is made better by doing so in a nontraditional fashion. So, in order to facilitate that, we’ve created an entire guide full of all the fun things we could think of to celebrate Chatham history! The guide itself, at present, contains virtual puzzles, coloring sheet downloads, Zoom meeting backgrounds, and BuzzFeed quizzes, and we’re adding new things all the time. All of the materials on the guide feature either photos from our collections, or information that we learned by looking at the primary sources in our collections. Links are provided to where those collections are housed virtually whenever possible. You can access the guide itself here. We hope you enjoy exploring and playing on the guide. If you have any questions, or even a suggestion for something to add to the guide, feel free to contact the archives using contact info on the Archives home page.

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

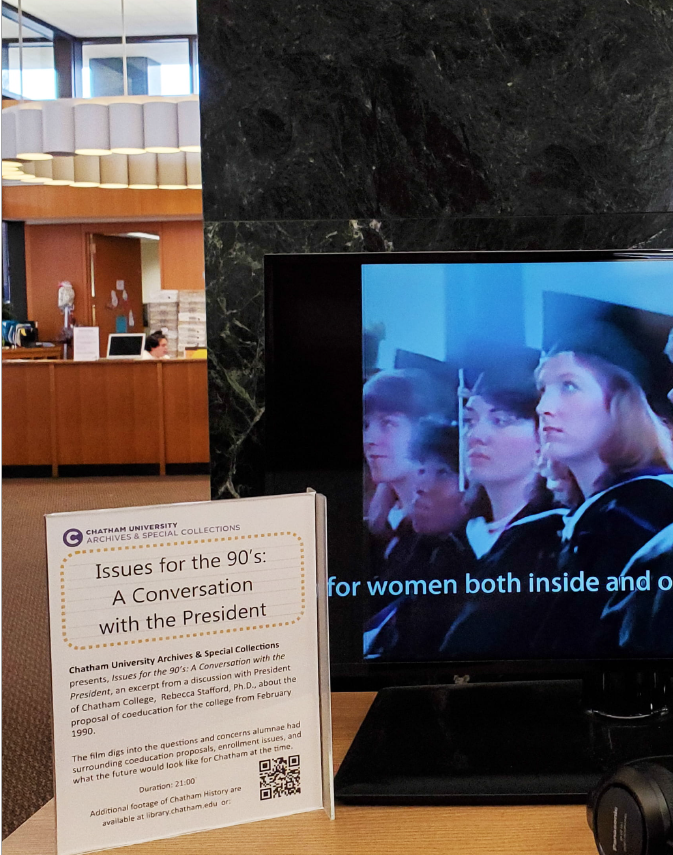

Archival footage on display in the JKM Library As part of an ongoing, rotating showcase of recently digitized media in the lobby of the JKM Library, the Chatham University Archives & Special Collections is pleased to present “Issues for the 90s: A Conversation with the President.” This film features Dr. Rebecca Stafford, President of Chatham from 1983 until 1990, discussing a proposal for coeducation brought forth to the college community in 1990. The footage was reformatted through support from the Council of Independent Colleges.

Members of the Chatham community and the public are welcome to enjoy the presentation.

The film digs into the questions and concerns alumnae had in the 1990s about the coeducation proposal, enrollment issues, and the future of Chatham College (now University). According to the footage, coeducation was being considered because of concern about enrollment projections and a desire to sustain the institution. Dr. Stafford mentions that growth in adult education at women’s colleges, like the Gateway Program at Chatham, served to increase enrollment numbers overall but did not provide a sustainable model over the long term. Rather, she concluded, Chatham needed to develop a plan to attract more residential students. Moreover, it is illuminating to learn that coeducation had been considered several times over the course of Chatham’s history. The footage of Dr. Stafford was recorded in February of 1990, a full twenty-five years before Chatham’s undergraduate programs became coed. The Coeducation Debate Collection (click here for the finding aid) includes records of the first formal consideration of coeducation at Chatham in the late 1960s and petitions from faculty, students, and alumnae when the issue was raised in 1990. In the footage on view, Dr. Stafford mentions that Board of Trustees discussed coeducation when changing the school’s name from The Pennsylvania College for Women to Chatham in the 1950s. She notes the trustees were concerned that Chatham must “have a name that doesn’t have `women’ in it."

Board of Trustee Minutes from 1954 discussing coeducation.

The “Issues for the 90s: A Conversation with the President” is on view in the JKM Library lobby for the enjoyment of members of the public and the Chatham

community. Those interested in exploring the history of coeducation at Chatham are encouraged to explore the film and related material in the Chatham University Archives and Special Collections.

By Janelle Moore, Archives Assistant, and Molly Tighe, Archivist & Public Services Librarian

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

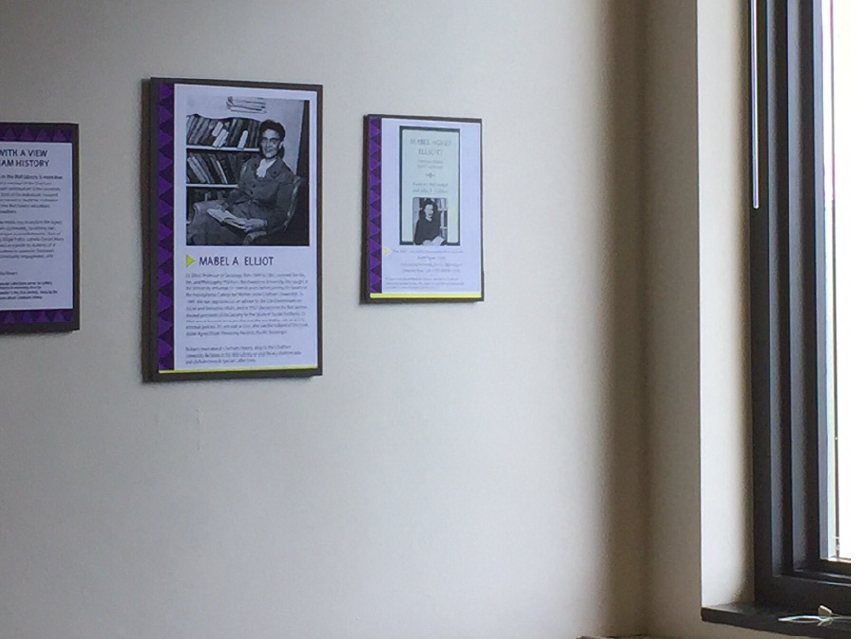

Have you ever noticed that a few of the group study rooms in the JKM Library are named? Have you ever wondered why or whom they are named for? The Chatham University Archives & Special Collections is thrilled to help solve these questions with our new exhibit, A Room with a View to Chatham History, which explores the lives of the individuals who’ve been honored with a room named in their honor at the JKM Library. History on view in the Elliott Room, JKM Library With this exhibit, on view in each of the named study rooms, we invite you to explore the legacies of Dr. Mary A. McGuire, Dr. Mable A. Elliot, Dr. Edgar M. Foltin, Laberta Dysart, and Arthur L. Davis. Each of these Chatham professors made significant contributions to their field of expertise and contributed to the development of Chatham as we know it today. Dr. Mable Elliot and the Elliot Room One of the most notable professors honored as the namesake for a study room is Dr. Mable A. Elliot, Professor of Sociology from 1949 until 1965 (Room 201). Dr. Elliot earned three degrees from Northwestern University (bachelor of arts, master of arts, and doctor of philosophy). Appointed as an adviser to the U.N. Commission on Social and Economic Affairs, Dr. Elliot was also the first women elected president of the Society for the Study of Social Problems (click here for more info). Dr. Elliot was described as both a feminist and a pacifist, and her criticism of U.S. criminal policies and anti-war activism led to the creation of an FBI file which was maintained for over 30 years. Interested in learning more about Dr. Elliot? Biography of Dr. Elliot in the JKM Library book collection Take a look at the book Mabel Agnes Elliott: Pioneering Feminist, Pacifist Sociologist in the JKM Library collection (click here to find it in the library catalog). Laberta Dysart and the Laberta Dysart Study Room Some members of the Chatham Community may be familiar with Laberta Dysart, namesake for Room 202, as author of the first history of Chatham, Chatham College: The First Ninety Years (available online through the University Archives here), but her contribution to Chatham does not stop there. A professor of history at Chatham from 1926 until 1958, she was active in Chatham’s Colloquium Club and in the local chapter of the American Association of University Professors. The University Archive’s Laberta Dysart Collection, click here for the collection finding aid, contains a variety of records documenting her impact on the university, including an article from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette about her retirement, an award honoring her service to Chatham, and the eulogy delivered by a former student and longtime friend, Eleanor Bartberger Dearborn `31, at a campus memorial held in her honor. Pittsburgh Post Gazette article in honor of Labaerta Dysart’s retirement. Chatham College Centennial Award given to Laberta Dysart Eulogy for Laberta Dysart written by Eleanor Barbeger Dearborn ’31 The Chatham University Archives welcomes further research on these individuals, on the history of campus, and how the Chatham community continues to shape the environment. Stop by the library to view A Room with a View to Chatham History or contact the University Archives at x1212 or M.Tighe@chatham.edu for more information.

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

Have you ever wondered what kind of stuff we keep in the University Archives? Been curious if there is anything other than letters, photos, and newspapers being saved as part of the record of the university? Now is your chance to find out! A new exhibit, Objects of Study: Selections from the Artifact Collections at the Chatham University Archives, is on view in the lounge of the Women’s Institute. Stop by the exhibit to explore the role played by artifacts and objects in documenting the history of the university and to discover some truly remarkable stories about campus, Chatham alums, and more. One of our favorite items on view is a copper coffer that was retrieved from the cornerstone of the old Dilworth Hall when it was demolished in 1953. “Dilworth Hall demolished? But, what’s that building just up the hill from the Carriage House?” you might ask. That’s actually Dilworth Hall II! The first Dilworth Hall, Dilworth Hall I, was attached to Berry Hall I. Here’s a picture of both halls as they appeared in a 1906 issue of Sorosis, the student magazine of the day: View of Dilworth Hall I and Berry Hall I at PCW in 1906 Both Dilworth Hall I and Berry Hall I were demolished in 1953 to make way for the upgraded academic buildings we still use today: Braun, Falk, and Coolidge. Here’s a couple photos of the demolition: View of Demolition of Berry Hall I and Dilworth Hall I at PCW in 1953 View of Berry Hall I and Dilworth Hall I during demolition with Chapel steeple visible in background I bet you are wondering what was found inside the copper coffer, right? Check out this article from The Pittsburgh Press (another relic from a bygone era) and read about the discovery. Newspaper clipping about PCW time capsule discovery The exhibit, Objects of Study: Selections from the Artifact Collections at the Chatham University Archives , features little known bits of history about Berry Hall I, The Minor Bird, and campus dining. Intrigued? Here’s some pics to help wet your whistle: Alumnae Napkin Rings at from University Archives History of The Minor Bird Logo Check out the copper coffer and other relics from the history of our university in the Women’s Institute or stop by the University Archives in the JKM Library to further explore our history.

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

Have you ever wonder how Chatham got its name or why it was changed from Pennsylvania College for Women? If so, you might want to check out the article on the topic in latest Library Newsletter <click here>, which tells the tale of how the school came to cosider a name change, the various names considered, and the reception of

the name at the time.

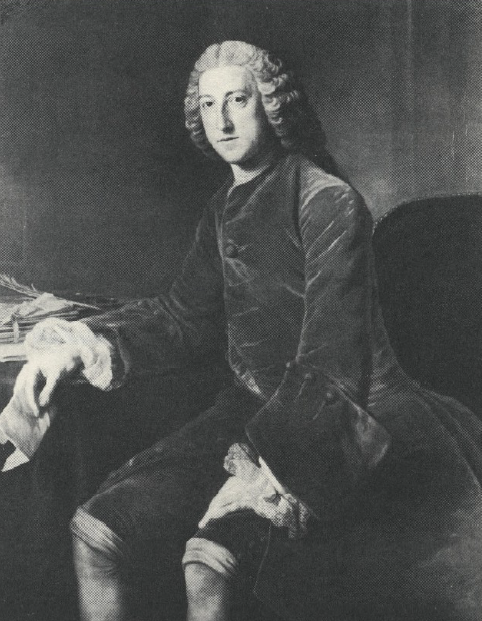

You’ll also want to take a gander at the images collected below. These selections from the collections of the University Archives illustrate how the school spread the word on the new name and all the events that surrounded this pivotal moment in university history. PCW officials chose to name the college after Lord Chatham in recognition of his passion for education and democratic ideals. On November 5, 1955, the school newspaper led with a bold headline announcing the name change from Pennsylvania College for Women to Chatham College.

David Lawrence, then-mayor of Pittsburgh, stands with Jane Stocker Burfoot from Chatham College’s Class of 1957. Together they are celebrating PCW having changed its name to Chatham College.

Students commemorate the name change by holding a Chatham College banner over the institution’s former PCW-marked entryway. The school produced this small brochure to promote awareness of the new name. The image above is the front cover. The brochure outlines the reasons for the name change and the reason for the selection of the name Chatham.

The brochure closes with an expression of Chatham’s continuing dedication to providing quality education.

A mailing card distributed to alumni around the time the college changed its name.

The front cover of the dedication dinner program, which took place two weeks after PCW changed its name to Chatham College.

…And just the day before, former US President Dwight D. Eisenhower commended President Anderson and the Chatham community on the college’s huge accomplishment!

We’ve got room for just one more picture…

This booklet was distributed to the Chatham community and alumni shortly after the institution changed its name. It contains personal remarks from then-President Paul

Anderson, Vice Chairman of the Board of Trustees George Lockhart, and Chairman of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development Arthur Van Buskirk on the role of the school in the intellectual and cultural life of the region.

Hungry for more history? Come see us during University Archives Office Hours on Mondays from 1:00 – 5:00 and Thursdays from 1:30 – 3:30 or by appointment. We’d love to share with you more about the name change to Chatham or any other aspect of university history you’re curious about!

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

Equal parts guidebook, GPS locator, and crowdsourced data platform, Clio is an app designed to help you discover local history. Named after the ancient Greek muse of history, Clio uses your location to provide information about nearby historical and cultural sites. Whether you’re a hardcore history buff or are just looking to get to know your city a little better, the network of professional and amateur contributors at work on improving Clio can point you to the important, unique, or just plain weird historical features of a city. You can also add your favorite historical sites to the map for everyone to see!

For new residents, Clio could help you catch up on your Pittsburgh history in no time. While on the Chatham campus, I found 43 sites within 10 miles of the JKM Library. Although there were a handful outside of the city proper, most were concentrated within an area easily navigable on foot or using public transit. Beyond addresses and

navigational content, entries tended to provide a robust about of information about individual sites; the records that I previewed included detailed historical descriptions (occasionally including citations), images, hours of operation, contact information, and links to outside resources.

In addition to currently operational historical sites such as monuments, historic buildings, and museums, Clio includes “Time Capsule” entries that point to sites where things happened or—particularly relevant to Pittsburgh—where things used to be. A pin at 6th and Wood downtown, for example, identifies it as the site of a “Protest Against Gimbels Department Store, 1935,” while another pin on South Bouquet Street marks the location of the former

Forbes Field. Whether you happen to be roaming the city or would like to plan your own historic Pittsburgh outing, Clio could be a useful tool for finding the hidden history all around the city.

Users can create accounts to help build the site database by adding and revising entries. All additions are subject to verification and approval, but the review process seems fairly transparent as revisions (even those by Clio administrators) are displayed in a change log at the bottom of the entry. According to the FAQ, entries are

published under a Creative Commons license that acknowledges the creator.

Because you can either search for a location or allow the app to use your GPS coordinates, Clio would work well both for travelers and for local exploration. In its best formulation, this crowdsourced data model could lead to some degree of local flair in terms of the sites included and their descriptions—after all, there’s no better way to

learn about a city than from the people that live there! Available for iOS and Android, and on the web.

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.

March 2012

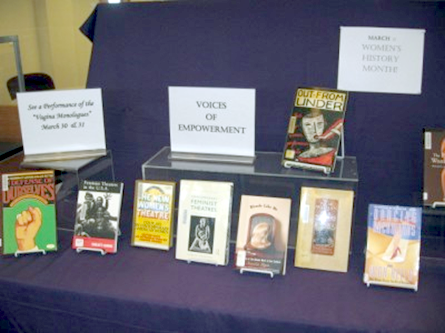

March 2012

Chatham is proud to be hosting two performances of the Vagina Monologues on March 3-31. Any and all donations will benefit Pittsburgh Action Against Rape (PAAR), which provides education, counseling, and a safe place for women who have been victims of sexual violence. The events, including the “Divas and Desserts After Party” are sponsored by the Office of Student Affairs and Feminist Activists Creating Equality (FACE)(see the March events calendar for details). The Vagina Monologues were created by Eve Ensler as a one-woman performance piece in 1996, as a way of empowering women and celebrating her individuality. This later grew to incorporate other performers and kick-started V-day, a global movement to end violence against women. Ensler uses her voice as empowerment, to speak about her own life and experiences, and bring to light the struggles and triumphs of women and girls worldwide, and to provide inspiration to others. Whether funny or harrowing, the monologues are always honest. In honor of Women’s History Month the Library will be highlighting women’s fight against degradation, sexual and physical violence, distorted body image, and using art as a tool and voice to raise awareness. While Ensler maybe the most popular contemporary face of women’s performance art, “The New Woman and her Sisters: Feminism and the Theater 1850- 1914” shows that the history is quite strong, using the stage to subvert male dominated and pervasive views of women in a time of feminist flux. A more recent title picks up in the 1970’s and 80’s during the second-wave and outlines the careers of performance innovators, the establishment of groups and their methods. “Out from Under: Texts by Women Performance Artists” is a collection of voices from marginalized groups, their common connection being that they are the largest group of “other”, women. It may be argued that some of this art is reactionary. Groups like the Guerilla Girls, point to female marginalization by hijacking galleries, reacting to the status quo. Artist Karen Finley, reacts to presentations of women’s bodies with her own body. But what all these women have in common is that they shine a light on women’s experiences and show it from a women’s point of view. Not surprisingly Finely (as well as Ensler), has been a source of outrage and criticism. “The Politics of Women’s Bodies: Sexuality, Appearance and Behavior” deals with how women’s bodies are seen and used by society and by women themselves, across the spectrum of age, class, and race. In light of recent political statements about contraceptives and other reproductive issues, this book is a must read. Check out our display and see what local groups like FACE and PAAR are doing to help women and girls in March and every day of the year.

The 1960s is recognized as a pivotal era in American history, when activists in the Civil Rights Movement worked to remove barriers to equality in the voting booth, the workplace, in banking, and more. But, how involved were Chatham students in these efforts? Some might recall that Chatham students joined the marches from Selma to Montgomery in 1965 and organized a campus visit by John Lewis in 1964, but when did they begin to participate in the movement? Using the recently digitized Chatham Student Newspapers Collection from the University Archives, we can explore how a student-initiated exchange program with Hampton University, a historically black college in Virginia, created opportunities for students to better understand racism in American culture and to engage more closely in efforts to dismantle Jim Crow segregation laws in the early 1960s. In March of 1961, the Chatham student newspaper (then called The Arrow) ran a front-page article about a seminar to be held at Hampton University (then known as Hampton Institute) on “African Nations in the World Community,” an event that invited interested students and faculty from other schools to attend[1]. Chatham students Dina Ebel `63, Helen Moed `63, and Janet Greenlee accepted the invitation and, upon their return, remarked that they were impressed by the “generosity shown by the students at Hampton” and “their keen interest in international affairs, even with a problem of their own race.”[2] The three students were highlighted in an article in The Arrow by Stephanie Cooperman `63 as a counterpoint to a sense of general apathy that she felt was affecting the Chatham student population. Cooperman wrote that more opportunities like the seminar at Hampton Institute would help to engage students in the world beyond the campus. She wrote, “Why not allow more of us to learn from actual experience the pain and courage it takes to live as a minority? Why not institute an exchange program, perhaps a week’s duration, with a Southern Negro college?”[3] Ebel, Moed, and Greenlee likewise supported the exchange program idea and wrote, “We had the opportunity and we want others to share our experience. You can’t just talk and write about it; you must live it.”[4] “[6] By the spring of 1962, an exchange program between Hampton Institute and Chatham College was in place. Those who were unable to travel to Hampton were invited to serve as hostesses for the Hampton Institute guests. This was the first such exchange program at Chatham and a variety of campus events, including dorm parties, a student-faculty tea, and a “folk sing at the Snack Bar” were planned to welcome the visiting students. The Hampton guests were encouraged to attend classes, student governance meetings, and on- and off-campus events of their choice.[5] Phyllis Fox`64, one of the five Chatham students to visit Hampton Institute in 1962, wrote in The Arrow that she hoped the program would “help bridge the wide gap of misunderstanding between beings of the same species.” Using poetry to express her thoughts, Fox wrote: “Every face has known joy and pain; Every face is wet with the same rain; The face is only the mask of life That hides the real human strife. A person is not a face, but a spirit and a mind So what matter if his skin is of a different kind?”[7] Winter of 1963 saw the HamptonChatham exchange program promoted in the student newspaper with an article describing it as an opportunity for “discussions on segregation with students who had led or participated in sit-downs and other integration movements in the South” and for insight into “one of the foremost problems of today, that of racial relations.”[8] After visiting Hampton Institute that year, Carol Sheldon `66 wrote about participating in a protest and learning about segregated lunch counters and employment discrimination. She wrote, “There is a certain unity about a group of fifty Negroes and three whites who walk into downtown discrimination-ridden Hampton on a Sunday afternoon; perhaps we were partners in fear, since many of us had not picketed anything before and were slightly apprehensive.”[9] Articles in the student newspaper about the program document a range of responses, with students expressing interest in extending the exchange for a whole semester and also insinuating that the Hampton visitors were given a less than welcome reception on campus.[10] Philip A. Silk, an Assistant Minister from the First Unitarian Church, submitted a letter to the editor to The Arrow in which he describes the potential for the exchange program to create “intelligent follow-up projects as aiding groups such as the NAACP or the Urban League.” He continues, “But it can also lead to a feeling that you have done your part, having proved your liberalism in this brief event.”[11] At the start of the 1963-1964 year, The Arrow announced plans to host a bi-monthly exchange column with the Hampton Institute newspaper[12] and efforts to help organize an exchange program between Hampton and a nearby men’s school, Washington and Jefferson College.[13] The exchange that occurred in the spring of 1965 seems to be the last. Following the exchange that year, Leslie Tarr `68 reported that there was little discussion of civil rights on Hampton Institute campus because the administration “frowned” on student engagement in civil rights demonstrations.[14] That administrators discouraged student participation in civil rights demonstrations is surprising, especially considering that Hampton Institute President Dr. Moron arranged, in 1957, an on-campus position for civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks after her demonstration sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott and she was fired from her job.[15] Tarr also said that Hampton Institute students agree that “It’s the parents who are causing the trouble, and there’s hope for our generation.”[16] Illustration from The Arrow published on 4/9/1965 [18] Though it is unclear from the student newspapers exactly why the exchange program ended, it seems that Chatham students remained interested in discussing racism and civil rights issues with members of the Hampton Institute community. In 1966, the Chatham chapter of the National Student Association organized a week-long Civil Rights Forum with an aim to “broaden the exchange of ideas between Chatham students and students of other campuses.” Panelists included students from Hampton Institute, Howard University, Tuskegee Institute and Central State University as well as speakers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[17] By exploring the newly digitized student newspaper collection, a more vivid picture of the early 1960s on Chatham campus emerges. However, lots of questions—like why the exchange program ended and how the participants continued to engage in efforts to dismantle race-based discrimination— remain unanswered. This period in Chatham history evokes enduring questions that are critical to the fight for equality, including questions of authenticity and performativeness that circulate within contemporary anti-racist efforts. Though materials in the Chatham University Archives can’t answer all of these questions, they present an opportunity to examine how activism on campus has—and has not—changed over the years. The Chatham University Archives welcomes questions about using the collections; more information can be found at library.chatham.edu/archives.

Notes

1. “Hampton Institute Holds Conference on Africa,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), March 17, 1961, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

2. Dina Ebel, Helen Moed, and Janet Greenlee, letter to the editor, The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), May 12, 1961 on 05/12/1961, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

3. Stephanie Cooperman, “Student Slams Do-Nothings,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 28, 1961, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

4. Ebel, Moed, and Greenlee, letter to the editor, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

5. “Chatham Welcomes Eight from Hampton,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 13, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

6. Stephanie Cooperman, “Chatham Arts On Integration,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), February 16, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

7. Phyllis Fox, “People Are People From Va. To Pa.,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 27, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

8. “Hampton, Chatham Trade Students for Weekend,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), February 22, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

9. Carol Sheldon, “Chathamites at Hampton,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 12, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

10. “NSA Board Requests Reply From You,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania),May 10, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

11. Philip A. Silk, letter to the editor, The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), March 9, 1962, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

12. “Arrow States Policy,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), September 27, 1963, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

13. “Seven to Travel to Hampton, Va.,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), March 13, 1964, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

14. “Five Students Visit Hampton College On Annual 4-Day Exchange Program,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), April 9, 1965, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

15. William Harvey , “Hampton University and Mrs. Rosa Parks: A Little Known History Fact.” Hampton University Website. Hampton University. Accessed January 28, 2021. www.hamptonu.edu/news/hm/2013_0

16. “Five Students Visit Hampton College,” https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

17. “NSA to Sponsor Forum on Rights,” The Arrow (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), February 4, 1966, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

18. “Five Students Visit Hampton College,” https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.