January 2012

January 2012

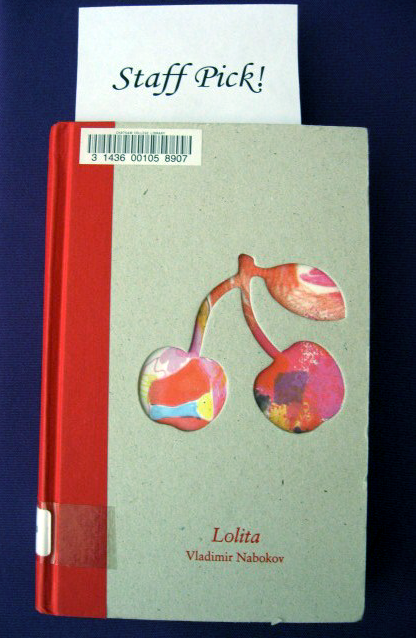

I chose to read Lolita in honor of Banned Books Week. I was as familiar with the storyline as anyone: an older man and young girl have a racy relationship. That, however, is really just a popular culture misunderstanding. Rather, what Lolita gives us is a portrait of a man: miserable, paranoid, desperate, and conniving. Nabokov offers a very pointed view into a dark place in a person’s mind and explores how one can be manipulative and manipulated, guilty, controlled, tyrannical, and weak.

I found myself wincing at times in the story. It is difficult to read a first-person narrative of an individual one finds so repellent and unsympathetic. Even as Humbert explains his behavior and attempts to understand his own psychology, it is hard to justify decisions and actions, but this is not Nabokov’s aim. The book opens with Humbert in prison, writing from memory his early life and the years he spent with his young victim. This I think offers the reader a sense that justice has been served on some level, a comfort in knowing that he does not ultimately “get away” with anything.

Nabokov’s prose is what makes this book so mesmerizing. Indeed, Lolita has one of the most famous opening lines in literature. The author’s neologisms, portmanteaus, and elegant turn of phrase carry the book’s difficult subject matter in a way that might be described as belle laide, beautiful-ugly. Perhaps like Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes. We are shown a horrific scene, but its execution is gorgeous. For a list of other works by Vladimir Nabokov, click here.

Reviewed by Donna Guerin, Reference Associate

January 2012

January 2012

2012 marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Silent Spring and the Jennie King Mellon Library is celebrating this milestone with a first floor exhibition of archival first editions, photographs, and papers from the Rachel Carson Collection housed in the Chatham University Archives. From now through January 30th, you can view images of Carson when she was a student at Pennsylvania College for Women in the late 1920s, a signed first edition of Silent Spring, a letter written by Carson, and materials documenting the book’s impact. The display also includes copies of Silent Spring available for checkout. One of the most important works of the twentieth century, Silent Spring was first serialized in three issues of The New Yorker beginning in June of 1962 and was published in book form later that year. Many cite the publication of Silent Spring, which called attention to the destructive impact of pesticides on our air, land, and water, as the foundation of the modern environmental movement. In response to the public outcry the book created, President John F. Kennedy formed a special government group to investigate the use and control of pesticides, and Carson testified before Congress in 1963 about new policies to protect the environment and the population. As a result of these efforts, DDT, a pesticide discussed in the book was banned in the United States in 1974, and the importance of conservation and environmental protection gained greater recognition in American life.

Commenting on blog posts requires an account.

Login is required to interact with this comment. Please and try again.

If you do not have an account, Register Now.